Introduction

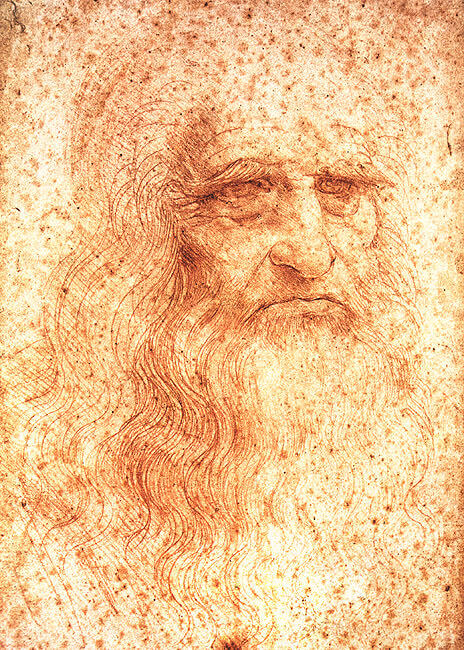

It is no question the impact that Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) had on the world of art, science, and technology during the Renaissance. What this website looks at are his anatomical drawings. These anatomical drawings are very mechanical in design, and it is almost as if he is drawing a machine but as a human. The question I wish to ponder is: Why did Leonardo da Vinci portray the human body as a machine during the Renaissance, which was generally a time that celebrated humanity and the natural human form? I will be arguing that da Vinci did not intend to distort the human body’s form, but instead wished to represent it merely in a different interpretation.

Context

First, some context is needed for the circumstances in which da Vinci created these drawings. The earliest known date of these kinds of drawings is 1487, and the last known date is 1513.[1] These drawings were created with a variety of materials and on different kinds of surfaces, however they were typically red or black chalk, pen and ink, silverpoint, or pastel, and on paper or other prepared surfaces.[2] In particular, the anatomical drawings were created along with active dissection of dead bodies done by da Vinci himself.[3] Some of them as well were not just humans, but other animals as well such as dogs or bears. Da Vinci is also known for many other styles of drawings, in particular his mechanical blueprints and propositions for various machines and mechanisms.

[1] A.E. Popham The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci (London: Random House, 1946), 59.

[2] Popham, 5-6.

[3] James Bruce Ross and Mary Martin McLaughlin, The Portable Renaissance Reader (New York: Viking Press, 1953), 535.

Primary Source Analysis

In terms of what Leonardo da Vinci himself wrote about anatomy and his drawings, I will be referring to a work of his titled Nature, Art, and Science (year unknown). In this work, da Vinci details why he studies and depicts anatomy. Within this work, he is responding to negative feedback given to him by writers and poets, as he has quite a defensive tone against them. Da Vinci challenges his critics to engage with the unsettling dead corpses if they truly wish to prove him wrong, and sums this up with stating that “you might not understand the methods of geometrical demonstration and the method of the calculation of forces and of the strength of the muscles; patience may also be wanting, so that you lack perseverance.”[1] He is clearly stating here that he sees the human body functionally the same as a machine or mechanism with moving parts and mathematical precision. He is also focusing on the inner workings of how the skeletons and muscles interact with each other in a geometric and mathematical sense.

When looking at his drawings, it can very much seem as if they are possibly inaccurate compared to what we know now about the human body’s form today. We know that da Vinci studied these dead bodies in great detail and had a lot of time on his hands to do so, but would he really have distorted them on purpose? Knowing who he was and what his other endeavors were, he also had an interest in machinery and engineering. What we are seeing when we are looking at Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings is simply another one of da Vinci’s designs, but with a human being as the basis. He mathematically refers to the “design” of the human body in terms of “height and position” and “proper proportions.”[2] He even refers to the inner workings of a human as the “mechanism of man.”[3] To da Vinci, the human body was nothing more than another moving machine.

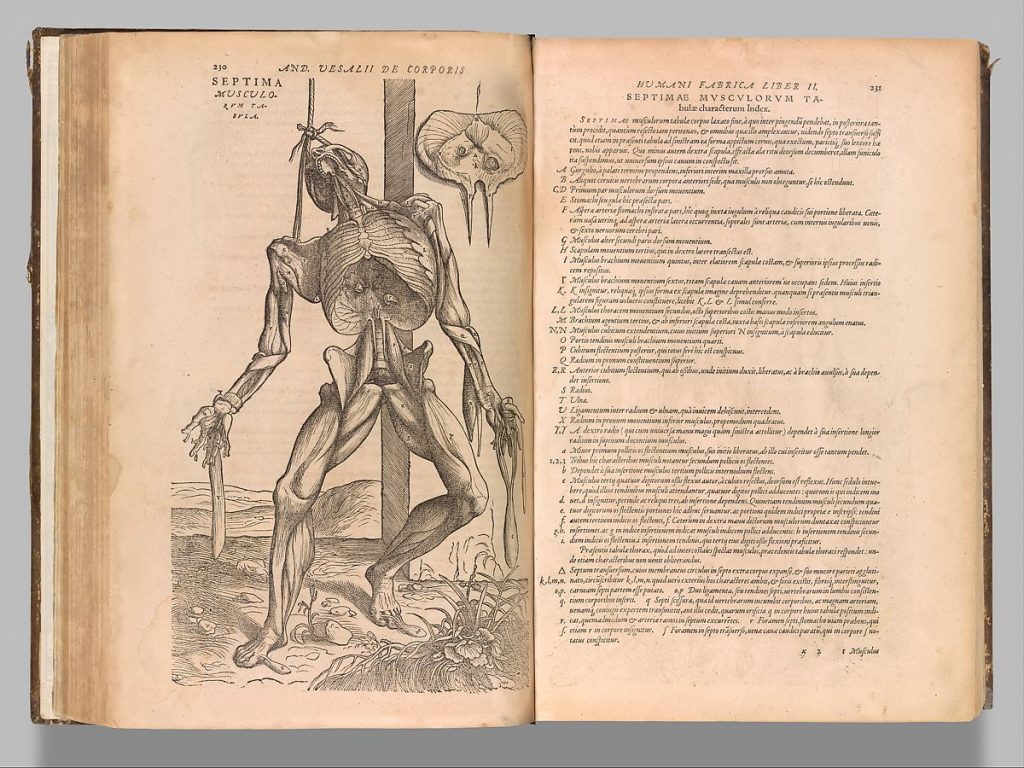

After da Vinci’s death, a Belgian physician named Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) continued where da Vinci had left off. One stark difference between the two was that whereas da Vinci had multiple interests beyond anatomy, Vesalius purely focused on creating anatomical drawings of the human body. Compared to da Vinci’s, his drawings are much fleshier and more expressive. In particular, Vesalius expresses fluidity in his human figures’ motions as opposed to da Vinci’s very rigid and mechanical design. Although they are fundamentally doing the same thing of drawing the human body, they are presenting it in a very different way. Da Vinci seems to be designing a human as if from nothing, and Vesalius is trying to present the true form of the human body.

In 1543, Vesalius addresses Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire in a letter describing his dissection efforts where he justifies his anatomical drawings in saying that they are a result of dissection, and wanting to further display accurate depictions of the human body: “[parts of the human body], they say, ought to be learned, not by pictures, but by careful dissection and examination of the things themselves.”[4] To Vesalius, it is as if his drawings are merely material to go along with his lessons and to further the learning of the human form in a medical sense. It is clear that knowing both Vesalius and da Vinci’s backgrounds and intentions, that Vesalius was more attempting to display the human body for use in the medical field and da Vinci was looking at the human body more as simply another design for him to create.

[1] Ross and McLaughlin, 536.

[2] Ross and McLaughlin, 537.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ross and McLaughlin, 569.

Historiography

In terms of how impactful these drawings that Leonardo da Vinci created were the author and compiler of The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, A. E. Popham (1889-1970), praises these drawings greatly: “The acuteness of his observation and the extraordinary accuracy with which he recorded what he had dissected, was far in advance of anything previously done.”[1] He also justifies presenting these drawings with wanting to highlight “Leonardo’s development as a draughtsman,” as opposed to the “scientific interest of his work.”[2] Meaning, Popham wishes to represent da Vinci’s anatomical drawings from an artistic perspective. As this was first published in 1946, perspectives on da Vinci’s drawings have greatly changed. A 2012 journal article by Domenico Laurenza aligns more with my argument of da Vinci wanting to present the human body as a machine. He argues that “Leonardo connected yet another typically anatomical-artistic area, the study of the human body’s static and dynamic equilibrium, with scientia de poneribus [science of weights], which at the time encompassed statics, dynamics, and kinematics.”[3] The author here is arguing that da Vinci was concerned with the engineering aspects of the human body, specifically the way that certain parts move and work together.

[1] Popham, 60.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Laurenza, Domenico. “Art and Anatomy in Renaissance Italy: IMAGES FROM A SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 69, no. 3 (2012): 13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23222879.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Leonard da Vinci presented the human body from a very different perspective. Rather than presenting it completely accurately like his paintings (or like some of his contemporary artists did), da Vinci wished to “design” the human body. He himself did a lot more than just anatomy, and as a result he merely saw humans as another machine that he could create on paper. This is opposed to Vesalius years later, who purely wished to depict the human body for medical purposes. However, da Vinci did not intend to distort the human body’s form. Rather, Leonardo da Vinci intended to present the human body’s inner workings as a machine akin to one of his designs.